MALDIVES

GREEN ROADS PROFILEThe ATO green roads profiles present country-level perspectives on how 35 Asia-Pacific economies are addressing the development and management of sustainable eco-friendly roads. Drawing from diverse datasets and policy documents, the profiles highlight practices and measures that contribute to greener transport infrastructure.

Developed by the Asian Transport Observatory (ATO) in partnership with the International Road Federation (IRF), the profiles are designed to complement the Green Roads Toolkit. The toolkit provides a practical reference for integrating good practices across nine dimensions:

- Decarbonization

- Climate resilience

- Water and land management

- Pollution reduction

- Conserving biodiversity

- Responsible sourcing of materials

- Improving quality of life

- Disaster preparedness

- Fostering inclusive growth

This 2025 edition builds on earlier work to provide a comprehensive resource for guiding the planning, development, construction, and management of greener, more sustainable roads.

Background

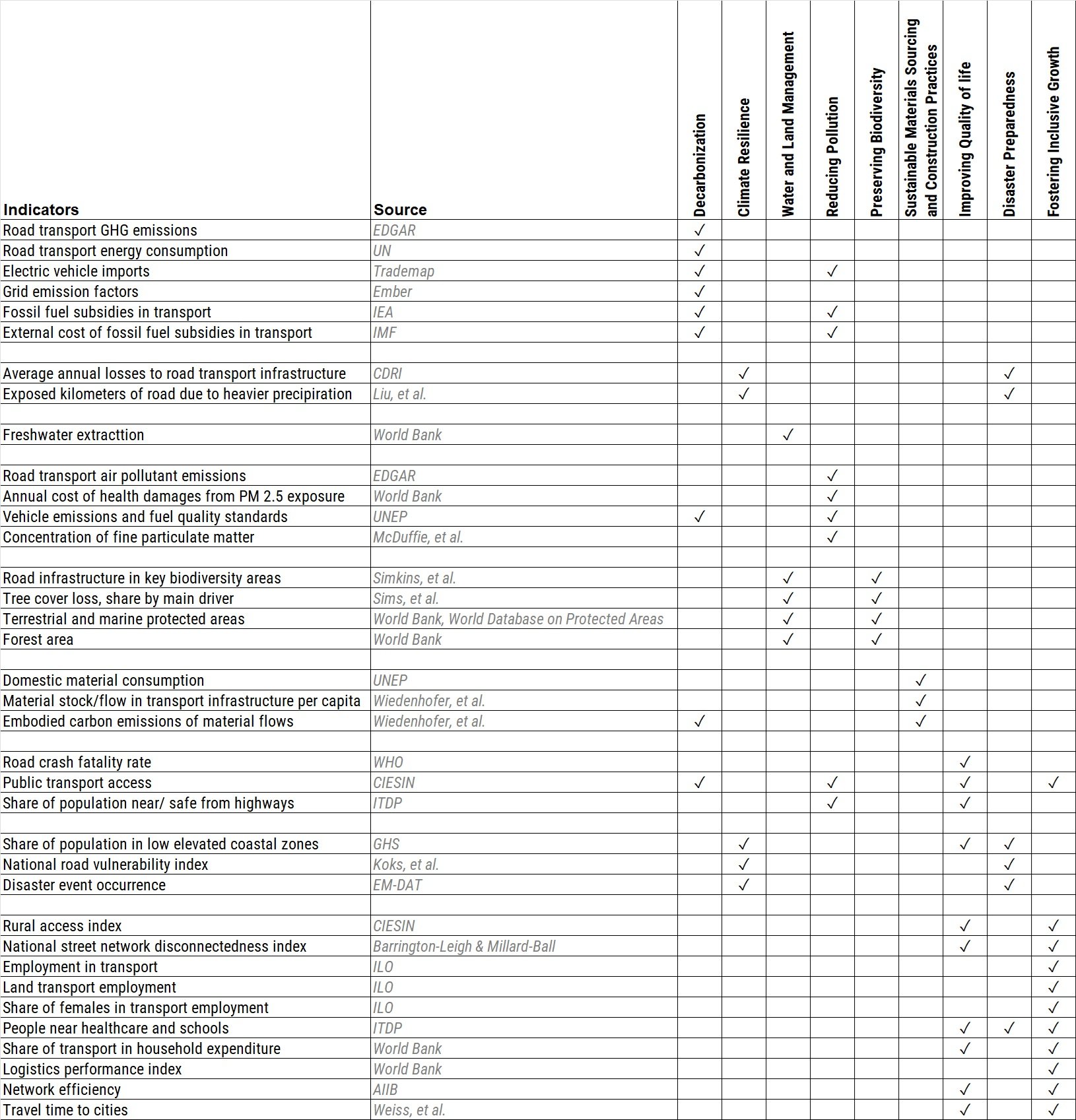

Indicator - Dimension Matrix

The Maldives' archipelagic geography, covering about 300 square kilometers, creates a unique disconnect between mobility needs and infrastructure capacity. The road network extends roughly 1,500 kilometers, with 96% serving local and rural areas. Despite the limited land, the density of this infrastructure is high, reaching 4,930 meters per square kilometer in 2024. Vehicle ownership has increased from 182 vehicles per 1,000 people in 2000 to 274 in 2024. While still below the Asia-Pacific average of 317, this growth trend indicates a nearing saturation of roadway capacity, highlighting the urgent need for policies that reduce dependence on carbon-heavy transportation expansion.

The carbon profile of the Maldivian transport sector exhibits concerning divergence from regional efficiency gains. Road transport GHG emissions reached 789 thousand tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) by 2024, driven by an annual growth rate of 6.6% since 2000. This acceleration outpaces the broader economy-wide emission growth of 4.7%, cementing road transport as a dominant pollutant source, responsible for 86% of total transport emissions and a staggering 38% of national economy-wide GHG output.

Critically, the emissions intensity relative to GDP has deteriorated. While the Asia-Pacific region averages an intensity of approximately 26 grams of CO2e per USD, and South Asia sits lower at 19 grams, the Maldives operates at 56 grams per USD. Despite a modest improvement in intensity of -3.7% per year since 2015, the pace lags significantly behind the regional benchmarks of -5.4% (Asia-Pacific) and -5.5% (South Asia). This efficiency gap is partially sustained by distortive fiscal structures; fossil fuel subsidies for transport incur substantial external costs, manifested in road crashes (27% of external costs), congestion (62%), and infrastructure damages (11%).

Two-wheelers dominate the modal share, comprising 85% of the fleet, a composition that offers a unique leverage point for rapid electrification compared to four-wheeler-centric markets. Light Duty Vehicles (LDVs) account for 10%, with buses and trucks constituting the remainder. The transition to electric mobility shows nascent momentum. Cumulative Electric Vehicle (EV) imports valued at 25 million USD were recorded between 2015 and 2024, capturing 9% of total road vehicle imports by the end of the period. The import mix is skewed towards LDVs (54%) and two-wheelers (36%). UNEP E-mobility Readiness Index assigns the Maldives a score of 51 out of 100, with critical deficiencies in policy frameworks.

Physical asset vulnerability in the Maldives is acute, characterized by high exposure to hydrometeorological hazards. The country faces potential average annual losses to transport infrastructure estimated at 64.8 thousand USD. While this represents a negligible fraction of GDP, the distribution of risk is highly asymmetrical. Bridges and tunnels, despite accounting for merely 0.1% of the road infrastructure stock, bear 100% of the projected losses from specific climate stressors.

This vulnerability is compounded by the material intensity of the network. The current road stock embodies approximately 4.9 million tonnes of material, with 73% locked in local and rural roads. Expansion and maintenance demand an additional 125 thousand tonnes of material annually, translating to 4 thousand tonnes of embodied CO2 emissions. Resilience planning must therefore integrate material efficiency to mitigate both physical risk and the carbon footprint of adaptation.

The external costs of the current transport model extend beyond carbon. Ambient air pollution, specifically PM 2.5, imposes a health burden valued by the World Bank at 159 million USD annually—roughly 2% of GDP. Transport sources contribute 22% of these emissions. While road transport PM 2.5 emissions have seen a marginal reduction of 0.2% per year since 2015, the aggregate concentration levels (9.6 micrograms per cubic meter in 2019) continue to drive premature mortality.

Road crash fatalities were estimated at 7 in 2021.Road crashes pose a substantial economic burden on the Maldives. In 2021, fatalities and serious injuries cost an estimated 41 million USD, roughly 1% of the nation's GDP.

Accessibility metrics reveal sharp spatial inequalities. While urban density is high, connectivity remains fragmented. Approximately 17,000 rural residents reside beyond the reach of all-season roads (defined as within 2 kilometers), effectively isolating them from essential services and markets. This isolation exacerbates vulnerability to external shocks and hampers disaster recovery. Furthermore, 58% of the population requires travel times exceeding 30 minutes to access major urban centers, indicating significant friction in regional connectivity.

The intersection of linear infrastructure and biodiversity is critical in a limited-land ecosystem. Research identifies that road infrastructure encroaches upon Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), with an equivalent density of 356 meters of road per thousand square kilometers of KBA. This is markedly higher than the South Asia average of 91 and the Asia-Pacific average of 88, signaling a high conflict potential between connectivity mandates and conservation imperatives.

The Maldivian road transport sector stands at a critical juncture where high asset density meets accelerating carbon intensity. The divergence between national emission trends and regional efficiency benchmarks highlights the urgency of reforming fossil fuel subsidies and accelerating the electrification of the two-wheeler fleet. Resilience strategies must pivot from general capacity expansion to targeted hardening of critical nodes—specifically bridges—which face disproportionate climate risks. Simultaneously, addressing the "last mile" deficit for the 17,000 isolated rural residents is essential to ensure that the transition to green roads is socially inclusive.

Decarbonization

Climate Resilience

Water and Land Management

Reducing Pollution

Preserving Biodiversity

Sustainable Materials Sourcing and Construction Practices

Improving Quality of life

Disaster Preparedness

Fostering Inclusive Growth

Supporting Information

Road Infrastructure Pipeline

| Addu Link Road Development | 2025 | 829 million MVR | 85.38 |

Unit Cost Road Projects

Road Transport Policy Landscape

Road Transport Policy Targets

| Strategic Action Plan 19-23 | 2023 | By 2023, vehicle congestion in Greater Male’ Region is reduced by 30% compared to 2018 levels |

Road Transport Policy Measure Types

References

AIIB. (n.d.). MEASURING TRANSPORT CONNECTIVITY FOR TRADE IN ASIA. https://impact.economist.com/perspectives/sites/default/files/eco141_aiib_transport_connectivity_4.pdf/

Asian Transport Observatory. (2025). Asia and the Pacific's Transport Infrastructure and Investment Outlook 2035. https://asiantransportobservatory.org/analytical-outputs/asia-transport-infrastructure-investment-needs/

Barrington-Leigh, C., & Millard-Ball, A. (2025). A high-resolution global time series of street-network sprawl. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23998083241306829

CDRI. (2023). Global Infrastructure Risk Model and Resilience Index. https://giri.unepgrid.ch/

CIESIN. (2023a). Rural Access Index [Dataset]. https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/sdgi-9-1-1-rai-2023

CIESIN. (2023b). SDG Indicator 11.2.1: Urban Access to Public Transport, 2023 Release: Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (SDGI). https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/sdgi-11-2-1-urban-access-public-transport-2023

EDGAR. (2025). GHG emissions of all world countries: 2025. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/9816914

Ember. (2024). Electricity Data Explorer [Dataset]. https://ember-energy.org/data/electricity-data-explorer

EM-DAT. (2025). EM-DAT - The international disaster database. https://www.emdat.be/European Commission. (2024). Global Air Pollutant Emissions EDGAR v8.1 [Dataset]. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset_ap61#sources

IEA. (n.d.). Fossil Fuel Subsidies. IEA. Retrieved April 19, 2025, from https://www.iea.org/topics/fossil-fuel-subsidies

ILO. (2025). ILOSTAT [Dataset]. https://rplumber.ilo.org/files/website/bulk/indicator.html

ITDP. (2024). The Atlas of Sustainable City Transport. https://atlas.itdp.org/

Koks, E., Rozenberg, J., Tariverdi, M., Dickens, B., Fox, C., Ginkel, K. van, & Hallegatte, S. (2023). A global assessment of national road network vulnerability. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 3(2), 025008. https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/acd1aa

Liu, K., Wang, Q., Wang, M., & Koks, E. E. (2023). Global transportation infrastructure exposure to the change of precipitation in a warmer world. Nature Communications, 14(1), 2541. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38203-3

McDuffie, E. E., Martin, R. V., Spadaro, J. V., Burnett, R., Smith, S. J., O'Rourke, P., Hammer, M. S., van Donkelaar, A., Bindle, L., Shah, V., Jaeglé, L., Luo, G., Yu, F., Adeniran, J. A., Lin, J., & Brauer, M. (2021). Source sector and fuel contributions to ambient PM2.5 and attributable mortality across multiple spatial scales. Nature Communications, 12(1), 3594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23853-y

Parry, S. B., Antung A. Liu,Ian W. H. (2023). IMF Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/publications/wp/issues/2023/08/22/imf-fossil-fuel-subsidies-data-2023-update-537281

Simkins, A. T., Beresford, A. E., Buchanan, G. M., Crowe, O., Elliott, W., Izquierdo, P., Patterson, D. J., & Butchart, S. H. M. (2023). A global assessment of the prevalence of current and potential future infrastructure in Key Biodiversity Areas. Biological Conservation, 281, 109953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.109953

Sims, M., Stanimirova, R., Neumann, M., Raichuk, A., & Purves, D. (2025). New Data Shows What's Driving Forest Loss Around the World. https://www.wri.org/insights/forest-loss-drivers-data-trends

Trademap. (2025). Trade Map. Trade Map. https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx

UN DESA. (n.d.). Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Indicators. Retrieved January 26, 2026, from https://policy.desa.un.org/themes/least-developed-countries-category/ldc-identification-criteria-indicators/evi-indicators

UN DESA. (2025). 2024 Revision of World Population Prospects. https://population.un.org/wpp/

UN Energy Statistics. (2025). Energy Balance Visualization [Dataset]. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/energystats/dataPortal/

UNEP. (2021, May 12). Domestic material consumption (DMC) and DMC per capita, per GDP (Tier I). https://www.unep.org/indicator-1222

Weiss, D. J., Nelson, A., Gibson, H. S., Temperley, W., Peedell, S., Lieber, A., Hancher, M., Poyart, E., Belchior, S., Fullman, N., Mappin, B., Dalrymple, U., Rozier, J., Lucas, T. C. D., Howes, R. E., Tusting, L. S., Kang, S. Y., Cameron, E., Bisanzio, D., … Gething, P. W. (2018). A global map of travel time to cities to assess inequalities in accessibility in 2015. Nature, 553(7688), 333-336. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25181

WHO. (2023). Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/safety-and-mobility/global-status-report-on-road-safety-2023

Wiedenhofer, D., Baumgart, A., Matej, S., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Lanau, M., Tingley, D. D., Liu, Z., Guo, J., Tanikawa, H., & Haberl, H. (2024). Mapping and modelling global mobility infrastructure stocks, material flows and their embodied greenhouse gas emissions [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139742

World Bank. (2021). ICP 2021. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/icp-2021

World Bank. (2022a). Annual freshwater withdrawals, total (% of internal resources) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org

World Bank. (2022b). Land area (sq. Km) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org

World Bank. (2022c). The Global Health Cost of PM2.5 Air Pollution: A Case for Action Beyond 2021. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1816-5

World Bank. (2023). Forest area (% of land area) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.FRST.ZS

World Bank. (2024). Home | Logistics Performance Index (LPI). Logistics Performance Index. https://lpi.worldbank.org/

World Bank. (2025a). GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD

World Bank. (2025b). GDP, PPP (current international $) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD

World Database on Protected Areas. (2024). Protected Areas (WDPA) [Dataset]. https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/wdpa?tab=WDPA